by Amani Dhifaoui

After the deadly robbery of an Armenian jewelry store in Beirut in 1985, the perpetrators of the crime, escaped from prison, rebuilt their lives as jewelers in Vienna.

Since 2017, the families of the victims have been trying to seek justice in the Austrian courts.

On this Tuesday in January, in a gray street in Vienna, Annie Kurkdjian slows down her steps.

She stops on the sidewalk. "I won't come any closer,” she said, “this guy’s face is the last one my father saw before he died, I don't want to see him." She came to the Austrian capital for this. To move forward the investigation that targets the assassin of her father. After years of investigation marked by extraordinary coincidences and incredible adventures, Annie Kurkdjian knows where to find him.

In March 14, 2023, the french Libération journal, published the following article signed by Amani Dhifaoui.

This face she does not want to see is that of George Mazbanian, alias Panos Nahabedian, owner of a jewelry store. It was also to find his trace that she made the trip from Beirut and accepted that Liberation would accompany her.

This visit around his shop is a pilgrimage. A way to remember “everything he took from me”, she says.

Annie Kurkdjian, in her fifties, was 12 when Panos Nahabedian and his two brothers, Raffi and Hratch Nahabedian, were charged with the murder of her father and his four employees. She grew up with the weight of this crime, a solved case, apparently without intrigue: she knows who killed, she knows why, she knows how.

Her quest is not for truth, but for justice.

The story begins on March 28, 1985 in Lebanon. In the heart of the Armenian district of Bourj Hammoud, three armed individuals break into the workshop of a jeweler, Hrant Kurkdjian. They shoot him and his four employees and leave with a loot of gold, diamonds, and cash. A robbery estimated at the time at 2 million dollars.

The next day, "the bloodiest crime in the history of Lebanon", according to the Lebanese daily L’Orient-le Jour, made the headlines, relegating the horrors of the civil war to the background.

The days following the massacre and until the arrest of the perpetrators, the whole country – resigned to burying the dead of the war but certainly not those of a heinous crime – lives to the rhythm of the police investigation relayed in the newspapers in its smallest details. The Armenian diaspora in Bourj Hammoud is deeply scarred by the savagery of the crime and overwhelmed by fear for the reputation of its community, already despised. Especially since It is subject to banal racism in this multi-confessional society. “Before the arrest of the assassins, we said to ourselves: Please God, make sure that the killers are not Armenians!” says Maro, the daughter of one of the victims.

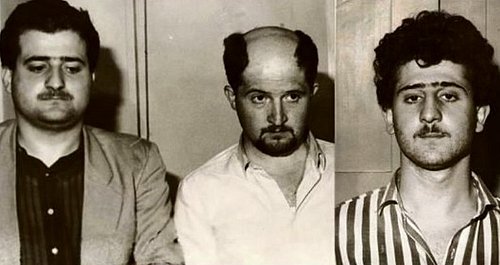

Fifteen days after the crime, two men were finally arrested in Lebanon and, some time later, a third one in Cyprus. They are three Armenian brothers, Panos Nahabedian, 27, Raffi Nahabedian, 23, and Hratch Nahabedian, 20.

Part of the loot is found in Raffi's apartment. After changing stories over the interrogations, the three men end up confessing to the crime.

According to their final version, it would be the youngest of the three, Hratch, who shot Hrant Kurkdjian and his four employees: Khatoun Tekeyan, Maria Mikhaël, both accountants, Hani Zammar and Avedik Boyadjian, employees. The motive of the crime : the indebtedness of the 3 brothers and the urgent need to find funds.

The Nahabedian brothers knew Hrant Kurkdjian well. Hrant had founded in 1966 with a partner, the Middle East Diamond Company , of which the Bourj Hammoud workshop is a part. His business was flourishing and supported dozens of families in different jewelry trades: setting, polishing, goldsmithing, engraving… Several subcontracting craftsmen, including the three brothers, gravitated around the company. Their entry into the workshop on the day of the murder aroused no mistrust on the part of the victims.

The Mazbani jewelry store, which belongs to Panos Nahabedian, in Vienna. (Michael Rathmayr/Liberation).

While awaiting for the trial, the three brothers are transferred to Roumieh prison, in the east of Beirut, reputed to be one of the worst in the country, as much for its degraded facilities as for its overcrowded situation. Months pass, the civil war intensifies, marking the darkest years in the country's history. And the crime falls into oblivion. Until one morning in March 1988 when the Nahabedians made the headlines again: the three brothers had escaped from prison. In the old fashioned way, sawing the bars of their cells and tying sheets. They managed to cross a Chaotic Beirut, riddled with checkpoints, soldiers, armed gangs… before evaporating from the country.

A trial in absentia finally took place in 1994. The case was judged by the military court: Hratch Nahabedian, the one of the three brothers accused of having fired on the victims, according to the conclusions of the investigation, was a deserter soldier at the time of the murder. And it is also for this reason that the death sentence initially pronounced against the three defendants was commuted to a sentence of forced labor for life.

It was thought that the trace of the Nahabedians was definitely lost until one morning in September 2013. Annie Kurkdjian, who had become a painter, was in her Beirut studio when she received a phone call from her friend Armen (1). “Grégoire [1], an Armenian painter is passing through town, I would like to introduce him to you.” Appointment is made for lunch, but in the meantime Armen and Grégoire make the tourist trip which, for Armenians, necessarily passes through the Bourj Hammoud district. "This is where the bloody murder of 1985 took place, where Annie's father died along with four of his employees.”

Grégoire, taken aback, stops in front of the building. "You're not going to believe me, but I know the killers and I know where they are today," he reveals to Armen. “I was with a friend in a jewelry store run by two Armenian brothers in the 1st district of Vienna, in Austria, we drank a coffee on the floor of their shop,” says Grégoire. At the time, it was said in the Armenian community that the two committed an assassination in Bourj Hammoud in 1985 and that they escaped from prison afterwards”. When Annie finds Grégoire and Armen in a Beirut restaurant, she does not suspect for a moment that this meeting will change the course of her life. “That evening, I understood that the moment had finally come… All the events of my life appeared to me as a slow preparation for the fight that I was about to lead.”

The story of the three years that followed this meeting will one day serve as a lesson in investigation for amateur detectives. Social networks, community directories, schools, churches… Annie sifts through everything she finds online about the Armenians of Vienna: she compiles a file on the new Austrian life of the Nahabedians, their family, profession, friends... with one certainty, that of having finally found the assassins of her father.

She mobilizes the families of the other victims of Bourj Hammoud and creates an association in order to finally obtain justice. They are fourteen to have lost a father, mother, sister, brother, child or husband. Fourteen lives shattered, lived with the trauma of the sudden loss of a loved one. Determined to force destiny, and relying on Interpol arrest warrants issued after the judgment in absentia, the fourteen took the case to the Austrian courts.

Vienna, January 2023. In the pedestrian streets of the historic center, the sound of the bells of the Stephansdom cathedral mixes with the piano notes that escape from a half-open window. It is in this landscape that the Nahabedians have taken up residence. Based on elements of Lebanese and Austrian court files, Interpol notices and press clippings, Liberation traced the second life of the three brothers in the Austrian capital. Under three different surnames, they lived without ever being worried until 2017, when an investigation was opened by the Austrian judicial authorities.

The eldest, Panos Nahabedian, renamed George Mazbanian, is the one who came out of it the best. In 1998, he opened a jewelry store in the very chic 1st district of Vienna: “Mazbani, since 1998”. His business is prosperous, he would have become rich… by the sweat of his brow. Its precious stones and the orientalism of its jewelry attract international clients. According to the shop's Instagram page, the customers include singer Beyoncé or actress Melanie Griffith among other Vienna opera stars. He had two daughters: the first, Talar, was born in Lebanon three years before the Bourj Hammoud massacre. She appears as the manager of the family business. The second, born two months after the crime perpetrated by her father, died.

Raffi died of an illness in 2012. This very pious, even rigorous Orthodox Christian was said to have been a fan of self-flagellation and other masochistic practices in his youth. In Lebanon, he spent most of his time in church and challenged the priest with his biblical knowledge. In Austria, he would have converted and is buried today in a Protestant cemetery in Vienna. Very few details exist of his Viennese life. His son Assadour contacted by Liberation, said he knew nothing of his father's past.

Hratch Nahabedian, aka Hamayak Sermakanian, did not enjoy the same fortune as Panos Nahabedian. The police who searched his home report “a dilapidated and dirty apartment, old worn furniture”, reports the lawyer of the victims, MMag. Norbert Haslhofer. His own jewelry store no longer sells anything today, he would be a subcontractor in diamond setting for his older brother. He had three children.

Jewelry stores in Vienna are not open to passers-by. You have to ring the bell first, they look at you through the window, and if your face suits, they open the door for you.

We ring the bell of the Mazbani jewelry store. It is Talar, dressed in black, who examines us before remotely opening the door. Wide commercial smile, false eyelashes and very strong make-up, she quickly suspects that it is not for the sake of her jewelry that we are here. Behind the counter, a spiral staircase leads to a floor reserved for real buyers.

We introduce ourselves, without specifying the purpose of our visit. Talar tells us “to have clients all day” and “have no time to respond to journalists”. In the back room, we see a man, probably his father, sitting at his desk.

Looking older than his 64 years, Panos Nahabedian, white hair framing a brilliant baldness and glasses on the end of the nose, is on the telephone. He doesn't seem to take any interest in the conversation taking place a few meters away from him. "We will call you back if we have time”, says his daughter, sketching an increasingly embarrassed smile. "I can't help but think that [Talar] took my life," Annie told us a little later. She seems oblivious to her father's misdeeds. It is her who should go back and forth to the prison to see her father, rather than me who go back and forth to the cemetery to remember mine.”

According to MMag. Norbert Haslhofer, the lawyer for the fourteen plaintiffs, George Mazbanian has put all his property in the name of his daughter since he knows that his trace has been spotted.

Officially, it is her who manages all his affairs. And she takes her role very seriously.

Not far from there is the shop with the closed iron curtain of Hamayak Sermakanian, alias Hratch Nahabedian, condemned for having shot at the five of Bourj Hammoud. The jovial-looking man who welcomes us explains with a sorry look that he no longer sells anything and that his shop is closed. Asked about the case, he replies that he has nothing to say, and politely refers us to his lawyer.

The other Armenian jewelers of the 1st Viennese district interviewed by Liberation are not more prolific. The first, born in Istanbul and immigrated to Austria forty years ago, does not wish to talk about the past of the Nahabedian brothers. He refuses to name the facts. George Mazbanyan? He is a “friend” with whom he is also in business, “an honest man”. And even if he knows that there are legal proceedings against him, and that the police are investigating, he is not afraid that his own business will suffer from it. "It's been thirty years that the business is working, I don't see why it's going to stop today."

The second Armenian jeweler interviewed explains to us that he no longer maintains relations with George Mazbanian alias Panos Nahabedian. The 40-year-old man says he was shocked when he heard the story of the murder. But he refuses to say more. Personally, he does not feel concerned by this scandal, because even if he is of Armenian origin, he was born in Austria and considers himself fully Austrian. "I don't feel like I belong to the Armenian community," he explains. My father would certainly have more to say to you on this, the Nahabedian brothers worked in his jewelry workshop when they arrived in Vienna in the late 80s, but since their Lebanese past began to resurface, he no longer wants to deal with them. We want to keep our good reputation in the industry, we do not want our name or image to be associated with theirs.”

Two days later, we went for a second time to the Mazbani store.

In the meantime, the "Armenian phone" has apparently worked well.

By pressing the open button, Talar Mazbanian does not even give us time to talk: “I know why you are here, you are investigating my father, you went to talk to the other jewelers in the neighborhood. We have no comments." As she begs us to leave, her father, with a straight face, pulls out his cell phone and takes a picture of us in his jewelry store, which is full of surveillance cameras. The young woman tapping fingernails on the shop counter betrays a certain nervousness.

Talar Mazbanian justifies her refusal to speak to us by threats that her family would have received. She accuses the plaintiffs of being "liars", "psychopaths" who would like to harm her family and stalk them "everywhere in the world".

Threatening messages on social media were reportedly sent to various members of her family. Has she filed a complaint for what she describes as harassment? "Anyway, it's useless," she replies.

"They want to harm my family and I have nothing to say about a story that happened when I was 3 years old, a story where there are a lot of lies", but with "some truth", she agrees, but “God will reveal the truth, because there is a God above”. Her cell phone suddenly rings. She picks up. In a fraction of a second, she responds with an "ok" to her interlocutor before hanging up. And to beg us firmly to leave.

Head to the Mkhitarist church in Vienna, where Father Vahan Hovagimian officiates. On social networks, we see him in several photos in the company of the Nahabedian wives and grandchildren. Although the family appears to have been Orthodox in Lebanon, it is today with the Armenian Catholic Church of Vienna that their faith is expressed. The warm welcome that Father Hovagimian gives us does not hide his embarrassment each time we evoke the story of the crime. This Armenian priest who, after the genocide, crossed the same places as Panos Nahabedian, born in Syria, raised in Lebanon and then emigrated to Austria, categorically refuses to "talk about individuals". He wants to “protect the secrecy of confession”. Did they confess to him? we ask. “It was not me who collected their confession,” he replies. Were their grandchildren baptized in this church? "I didn't baptize them." "It's a very thorny story, and very private, it's not my role as a priest to play the role of Interpol", he says. But what about the victims? "I don't know the victims, it happened in Lebanon, it's far away," he judges. Father Vahan Hovagimian assures us, however, that since the press has been talking about the Bourj Hammoud crime, the Nahabedians “don't come to church anymore, they are underground”.

After lighting candles for peace, tasting the herbal liqueur of the Mkhitarist church, marveling at its century-old library, we leave the place even more perplexed as to the course of the Nahabedians since their arrival to Austria. Who helped them? How did they make their fortune? Silence is law in the community.

When the lawyer Norbert Haslhofer agreed to represent the fourteen victims in 2016, there were several unclear areas in the file. It was necessary to investigate to find the new identities of the fugitives, trace their family ties, identify their property... but the real hard part remains the transfer of the Lebanese file to the Viennese courts. The case is old, decades of war and corruption have crossed Lebanon. Floods and fires destroyed several parts of the file. It took some stubbornness to reconstruct the 1200 pages of an almost forty-year-old affair. And it takes even more today to manage the translation of these pages. Technically, this is what the Viennese public prosecutor's office is waiting for to decide on the follow-up to be given to the file. According to MMag. Haslhofer, the translation of the Lebanese file is about to be completed “from here a few weeks". Asked about the slowness of this translation procedure, which has been going on since 2017, Nina Bussek, spokeswoman for the prosecutor, explains that there is only one translator in Vienna authorized to translate "the Lebanese language" who, in addition to the substantial size of the file, had to deal with the theft of his computer containing documents relating to the case.

But it is to count on the dedication of the lawyer Haslhofer; "I knew that the criminal case in Austria was going to take years of investigation, and the possibility of extradition of the defendants is almost impossible since they have become Austrian citizens." So the council found the parade: a new complaint was filed to revoke the Austrian nationality of the two brothers still alive, given that they entered the territory with false identities. It is now done, first for George Mazbanian, the eldest, who has become Panos Nahabedian. And for his younger brother Hamayak Sermakanian, alias Hratch Nahabedian, who is believed to be the killer. “I am going to appeal the decision of nationality cancellation, without much conviction, declares the lawyer of the latter, Dr. Astrid Wagner, but I know that I'm going to lose."

Nestled in an old building in the 1st district, lawyer Wagner's office betrays her Francophile tropism. The fragment of a Bonaparte crossing the Great St. Bernard sits behind her back with images of cats, pop art posters and a framed archive article on London's greatest murderer of the 20th century. The one who keeps from her childhood in France an almost perfect mastery of French defends her client, "the poor" Mayak Sermakanian, alias Hratch Nahabedian. For her, he is "innocent, it was not he who killed the five victims". And although he made a confession, she believes that "his older brother has a bad influence on him, it was Panos who shot and not my client". In the case of a trial, will he testify against his brother? "I can't tell you anything about that."

Star of the bar in Austria for having defended notorious criminals, it is a completely different line of defense that she has chosen for her client: “He is an honest man but he is dumb” she says. If he wasn't stupid, he would have entered Austria with his true identity, even having committed a crime. In times of war, he would have obtained refugee status, he was not obliged to take on a false identity”. The lawyer has her own theory on the facts. “My client was tricked, his brothers tricked him into dangling a heist plan, there was not a matter of murder. He did not know there would be deaths, she explains. His brothers made him take the blame because he was a soldier and did not risk capital punishment.

If lawyer Wagner talks easily about the details of the case, it is because she knows very well that her client has nothing more to fear. "My success in this case is to have managed to get him out of the criminal record." Indeed, at the time of the events, in 1985, Hratch was 20 years old. For Austrian justice, concerning any crime committed before the age of 21, the perpetrator cannot be sentenced to a sentence greater than fifteen years in prison. The life sentence pronounced in Lebanon is therefore not recognized in Austria and the proceedings against him have stopped. And even if he is no longer protected by Austrian nationality, Dr. Wagner believes that he will never be extradited to Lebanon, because it is a country that does not respect human rights in her eyes. "Even Pol Pot would not be extraditable to Lebanon," she concludes.

So why does he refuse to speak on the case since he no longer risks anything? “He is afraid of his brother” continues master Wagner. He lives under the influence of the permanent fear of his brother, even his wife does not want him to have contact with him anymore.”

The older brother, Panos Nahabedian, who refuses to comment, instructed his lawyer not to communicate on the case. Contacted by Liberation, lawyer Manfred Ainedter, one of the most popular in Vienna, “does not wish to speak to this stage of the file, but perhaps later".

This indeterminate “later”, on which the mourning of fourteen people hangs, depends on the final point of the translation of the Lebanese file. According to MMag. Norbert Haslhofer, "once the translation is completed, the public prosecutor will have to respond to the extradition request made by the Lebanese courts, but this decision comes up against the human rights situation in Lebanon. The rule of international law requires a country that refuses to extradite an accused to try him on its soil. The Austrian case being about to be closed, it might be better for the Austrian justice to hold a trial here”, explains the lawyer. Only Panos Nahabedian is concerned because at the time of the crime he was over 21 years old, so the facts are not subject to any limitation period according to Austrian law. Remains the trail of civil proceedings, a complaint that lawyer Haslhofer is about to file. "If Panos is found guilty in Austria, the payment of compensation to the victims will be systematic."

Under a dark sky, Annie leaves her lawyer's office. Lost gaze, faded lipstick that draws a melancholic smile. “I still have come a long way compared to the first time I visited this office. While waiting to see [the Nahabedians] behind bars, I tell myself that I still managed to assign them the identity that they did everything to flee. They no longer have their identity papers with falsified names. They will forever keep their names of assassins.”

(1) The first names have been changed.