by Martin Staudinger

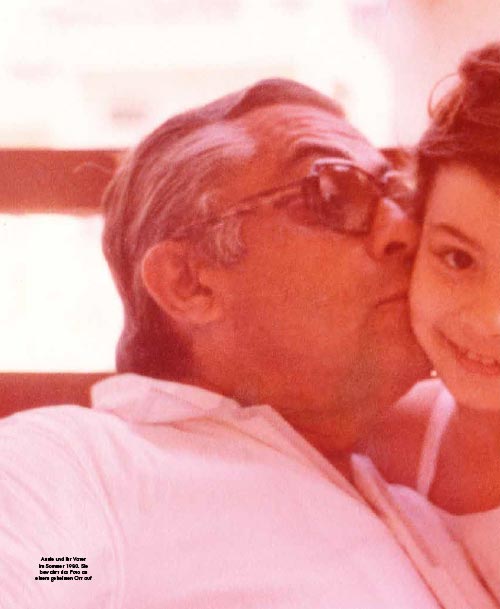

On March 28 1985, a 12-year-old girl stepped out of the door of her parents' home, in Beirut, early in the morning. Annie turns back to her father, who is standing at the top of the balcony, and briefly considers whether she should run back to catch up on the little farewell ritual that the two of them skipped today in their haste - a kiss on the cheek. But she's late, the school bus is waiting, exams have to be presented, and her father waves his hand at her to hurry up. She has no idea that at this moment she sees him for the last time.

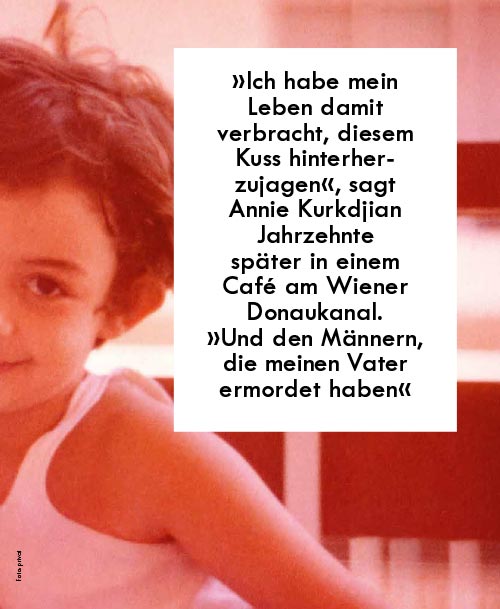

“I spent my life chasing that kiss,” says Annie Kurkdjian almost 40 years later in a Coffee shop on Vienna’s Danube Canal, looking out the window for a moment as snowflakes fade onto wet gray paving stones: “And the men who murdered my father.” This is the story of a hunt for three robber-murderers and a missed kiss; a hunt that has now lasted almost four decades and lead two continents, with prison breaks, falsified identities and a tombstone on which a fake name has been engraved in sentimental carelessness.

Half past three in the afternoon, Annie is back home. She sits at her desk and does schoolwork. Actually, the father should have been there long ago, he is never late. The bell rings, but there is obviously someone else at the door. Annie hears her mother talking, then anxiously speaking on the phone. It's better to stay in the children's room: these are matters concerning adults.

At four o'clock, the house was filled with relatives, Annie enters into the living room. She sees worry on their faces. The father's driver comes by, he also looks scared. “Something happened”, he says, but doesn't say what.

Five o'clock, an uncle drives off to finally find out what happened. At some point, it's already dark. He calls - there's been a shooting, but don't panic! Nothing serious.

Half past seven, the uncle came back. He struggled for words for minutes. And then he just said: “They’re all dead.”

The dead are: Hrant Kurkdjian, owner of the "Middle East Diamond Company" and his four employees - Hani Zemmar, Maria Hanna Mekhayel, Khatoun Tekeyan and Avedis Boyadjian.

The morning after, like every day, the newspaper is on the Kurkdjian family's doorstep. “Biggest robbery in Lebanon’s history,” on the headline.

The crime scene photos show the brutality with which the murderers who attacked the jewelry store in the Bourj Hammoud district acted. Hrant Kurkdjian kneels against the wall, his tie still tied correctly; Maria Hanna Mekhayel collapsed under her swivel chair, Hani Zemmar next to a desk on which there was a telephone that was not hung up. Khatoun Tekeyan and Avedis Boyadjian lie on their faces, on the floor, and there's blood everywhere.

The suspected perpetrators are quickly identified: Panos, Raffi and Hratch Nahabedian - three brothers from the neighborhood who sometimes do business with the jeweler and, like him, are members of the Armenian community in Lebanon: "Master, I have debts and you have money", Raffi said when he entered the shop - that's what he said in the first confession he made after his arrest. Then the shots were fired.

With bags full of gold, diamonds, precious stones and cash worth 20 million Lebanese pounds (equivalent to around 1.15 million dollars) - the three want to build a new life in Europe.

They don't get far. After a chaotic back and forth between Lebanon, Syria and Cyprus, they were arrested less than a week later. First it is Raffi, the middle of the three brothers, who confessed: he was the one who shot, says the 25 old man. Hratch then takes responsibility for the five murders. He is currently serving in the military and therefore, according to the Lebanese law at the time, unlike Panos and Raffi, he does not have to fear the death penalty.

The gates of the notorious Roumieh detention center northeast of Beirut close behind the three brothers. The hunt could end here: with verdicts and long prison sentences. However, the proceedings against them do not move forward. This is by no means because the judiciary is inactive: the case is being investigated meticulously. However, two months after their arrest, the three brothers create confusion. They claim to have committed the crime on behalf of Hrant Kurkdjian's closest business friend - although this later turns out to be a lie, it steers the investigation in the wrong direction. Panos, Raffi and Hratch Nahabedian have been imprisoned in Roumieh for three years without a trial. They prepare during this time, their escape. Then one day, on March 5, 1988, the bars in front of the windows of their cells were sawn through. The three have disappeared.

In the months and years after the crime, Annie sees how her family breaks up. The mother sinks into depression, the 16-year-old brother is consumed by his anger, and she feels guilty, angry, scared and lonely all at the same time. “It was as if I no longer had any skin to protect me,” she remembers 38 years later. There is no psychological help: At the end of the 1980s, the armed conflict in Lebanon escalated once again. In addition to the devastation caused by the civil war, the emotional damage caused by a single criminal case counts for nothing.

And yet the family is supposed to take care of the jewelry store, which contains 20 years of work from their dead father - and their own existence. Money, jewelry and precious stones that the trio robbers stole were recovered, but in a disastrous condition: the jewelry was dismantled, the gold was melted down, and diamonds and other precious stones were randomly stuffed into sacks. It takes the Kurkdjian family five years to take inventory. In the end it turns out that a large number of the valuables are missing.

The Lebanese civil war ended in 1990 after more than 15 years with a peace agreement: “But in my soul there was still war,” Annie says today.

Meanwhile, there is still no trace of Panos, Raffi and Hratch. After all: the judiciary has not forgotten the crime. In 1994, nine years after the Bourj Hammoud massacre, the brothers were convicted in absentia for murder. The death sentence that was initially passed against them was later commuted to life imprisonment with hard labor.

During this time, Annie learns to live with her father's death. She looks for psychological and theological answers to her questions, and she begins to paint: “Whenever my brush touched the paint, I was able to fly up from the abyss into which I had been thrown.”

The fact that rumors about the lonely, painful death of Panos, the eldest brother, are making the rounds in Beirut's Armenian community hardly bothers her. Sometimes she googles the last name of the perpetrator - but she would like to believe that the case no longer affects her. For almost two decades. Until one day in September 2013.

In June 1988, three months after the prison break in Beirut, three young men arrive in Vienna. They call themselves Hamayak Sermakanian, Harout Dayan and Asdghik Mazbanian - the authorities don't notice that Asdghik is a woman's name; that the newcomers' documents are forged. Hratch, Raffi and Panos are able to enter Austria undetected.

Documents from the Vienna immigration authorities suggest that they brought their families with them shortly afterwards and began working in the jewelry industry. At the beginning of the 90's they applied for Austrian citizenship. They justify this wish with the difficult situation in Lebanon and the hope of being able to offer their children a secure future.

In 1998, the next step towards respectability: the eldest and youngest brothers registered the Mazbanian & Sermakanian OEG at the Vienna Commercial Court, and they themselves acted as partners with unlimited liability.

In the following years, the Nahabedians established themselves in Vienna under the name Mazbanian. Panos, the oldest, is particularly successful. He rents a business premises in the center of the Austrian capital, a few minutes' walk from St. Stephen's Cathedral and the State Opera. Smaller and larger reports, especially in the gossip columns of the tabloid press, document how the family gradually arrives in better Viennese society.

“A real asset: The Mazbanians,” wrote the daily newspaper “Kurier” in 2014: “Their customers include not entirely poor Austrians, as well as magnates from the East and the Orient who fly to Vienna.” And sometimes even world stars stop by here. Melanie Griffith, for example, who bought a pair of earrings to wear to the opera ball in 2018. The jewelry was designed by Panos' daughter, as the free newspaper “Heute” reported at the time.

The jewelry company also demonstrates its social conscience: for example, with a special bracelet that was produced specifically for a large auction to benefit children's cancer charities. In the Armenian community in Vienna, people know about the dark past of the three brothers - but they don't talk about it openly.

It is an almost unbelievable coincidence that ensures that the hunt for Bourj Hammoud's murderers is resumed. One morning in September 2013, Annie, who now works as an artist, received a call from a friend - he wanted to introduce her to a painter who was stopping in Beirut after a trip to Europe. How about a meal together? Annie accepts without knowing what she will discover. The traveler has barely sat down at the lunch table when he says a sentence that stirs everything up again: “I think I know who killed your father.”

It turns out that the painter, also an Armenian (he wishes to remain anonymous), had visited Vienna eight years earlier. There, he says, an acquaintance showed him the city and also took him to an Armenian jewelry store. A nice chat with the owners, a cup of coffee, everything was very pleasant. But later, out on the street, his companion murmured something disturbing to him: the respectable solidity of the shop was deceptive, as the jewelers had killed several people in a robbery when they were young men in Lebanon.

And now, in Beirut, he learned how Annie's father died.

“I didn’t believe it at first,” says Annie: “I pushed the whole thing aside, but it still didn’t let me go.” She later sends the painter an email with the old mugshots of Panos, Raffi and Hratch. Shortly afterwards he replied: He was sure that he recognized at least two of the people.

Annie sits down at her computer and, after a long time, types the name Nahabedian into the search engine again. She doesn't hold out much hope - she assumes that the refugees have long since assumed a different identity. But after just a few clicks, she comes across the Facebook profile of a young man in Vienna who posts photos of family celebrations under the name Nahabedian. Balloons, flowers, cakes. Laughing faces. And in one of the pictures she recognizes Raffi, who is surrounded and kissed by his sons.

“Actually, I had already finished with the murderers. I found comfort in the idea that they ended up somewhere in Syria or Afghanistan during their escape and were vegetating there in misery," says Annie: "But these images of a good life in Europe - that was a provocation. The anger motivated me. I have decided to attack.” She begins to conduct targeted research on the Internet, searching social networks, telephone directories, and the websites of Armenian schools and churches in Austria. Over time, one mosaic piece at a time, something like a virtual mugshot of the person being sought comes together.

She gets in touch with the surviving relatives of the other victims of the massacre: 14 people who were robbed of their mothers, fathers, siblings or partners in the attack on the “Middle East Diamond Company” - or who had to grow up as orphans in the middle of the Lebanese civil war because their families are broken as a result of the crime. Now they are hopeful that they have found the murderers and can hold them accountable. But that turns out to be more difficult than expected.

Lawyer Norbert Haslhofer is initially skeptical when he receives a visit from a woman from Lebanon in 2016: Before he became an Independent lawyer, he worked as a public prosecutor for many years, primarily prosecuting white collar crimes - complex, dry white collar crimes, some of them with connections to high politics. The case that Annie Kurkdjian is now taking on him is in an area that hardened criminal defense lawyers are usually responsible for.

Lawyer Haslhofer becomes a detective. Together with Annie, he makes covert contact with Nahabedian family members on the Internet. Little by little, the two of them manage to map the relationships of the extended family - and in doing so, increasingly narrow down the three people they are looking for.

When it turns out that Raffi died in 2012, the lawyer sets out to find his final resting place. He walks the rows of graves in Vienna cemeteries until he comes across a memorial stone on which the name Nahabedian, the real name of the person he is looking for, is engraved. And next to it: a photo of Raffi.

“That was the moment when I knew: We got them,” says Haslhofer.

The criminal complaint that Haslhofer subsequently files leads, among other things, to Hratch's fingerprints being checked again. Result: He is undoubtedly one of the three men who were convicted of the robbery-murders in Lebanon in 1994.

The Bourj Hammoud massacre now has a first file number in the Vienna public prosecutor's office: 406 St 35/17y, suspected five-fold murder and aggravated robbery against the two surviving brothers Panos and Hratch, who now have Austrian citizenship.

But the process runs into difficulties right from the start. There are no direct witnesses to the murders; Investigators and prosecutors in Lebanon are now retired; Archives were devastated by fires and water damage; Files have to be found, sorted, brought to Austria and laboriously translated; Disasters such as the chemical fertilizer explosion in the port of Beirut in 2020 and crises such as the Covid pandemic are causing additional delays; in Austria the responsible public prosecutors change again and again; and strange things happen: For example, when the court interpreter's laptop on which all the documents and translations that have already been saved is lost - and he has to start all over again. The more time passes, the more complicated the evidence becomes.

Hratch, who took responsibility for the murders in Lebanon, now tells the story completely differently: He was at the crime scene, but mentally stepped away the second he heard shots - as a result of childhood trauma during the civil war: “When there was a shot, I was no longer with myself. I don't know what exactly happened or who shot. But I swear: it wasn’t me,” he assured in an interview with the Austrian magazine “Profil” in 2020. Then why did he admit everything? Beatings by the Lebanese police and a decision by the family council, which hoped that this would spare all three brothers the death penalty?

In addition, Hratch can no longer be prosecuted due to a peculiarity of Austrian criminal law - there is a situation in which even murder becomes statute-barred: if the perpetrator is not older than 21 at the time of the crime and is therefore a "young adult". If no proceedings are initiated against him within 20 years of the crime and he does not commit any other crimes, he will go unpunished. And that's exactly what applies to Hratch, who, according to his lawyer Astrid Wagner, no longer wants to give a comment on the case.

Raffi, who originally made the first confession, has died and can no longer be questioned. That leaves Panos, the eldest brother: although he committed the robbery in Lebanon, unlike the other two, he never admitted involvement in the murders. Now he is the only one still under investigation. Through his lawyer Klaus Ainedter, he declines to comment on the allegations. Panos is also tight-lipped with the authorities. When questioned by the Vienna police, he simply declared that he would not plead guilty. It had already been established in Lebanon that he did not shoot.

Late winter 2023, 38 years after the Bourj Hammoud massacre, a Coffee shop in Vienna's second district: Annie has never been as close to her father's suspected murderers as she was on this day. She spends her life between Beirut and France and only traveled to Vienna to meet lawyer Haslhofer and advance the case. Now all she would have to do is cross the Danube Canal and walk a few minutes through the city center to reach the jewelry store that Panos and his family run.

But she doesn't want that. It probably wouldn't do much good to show up at his door. Panos himself has so far always refused to say anything about the allegations. And his family seems convinced that Annie and the other survivors of the massacre victims are just liars and psychopaths.

Their efforts have now achieved one thing: Panos and Hratch have had their Austrian citizenship revoked. Extradition to a country like Lebanon seems hardly conceivable given the situation there. But if at some point all investigations in Austria are completed and a trial results in a guilty verdict, Panos will not only face many years in prison, but also possible claims for damages.

So what do the relatives hope for after such a long time? “It’s a question none of us can answer,” says Annie: “Would I find peace if Panos was in prison? No. Would I find peace if I got 20 million euros? No."

She thinks for a moment: “Every day I see the picture of my father dead on his knees. I would find peace if I had the feeling that his dignity would be restored. This is the only way I can tell him I love him.”

And in this way to give him the goodbye kiss.

View the original article in pdf (German)